Loxias-Colloques | 3. D’une île du monde aux mondes de l’île : dynamiques littéraires et explorations critiques des écritures mauriciennes

Françoise Lionnet :

Cosmopolitan or Creole Lives? Globalized Oceans and Insular Identities

Résumé

La réflexion critique sur les phénomènes de cosmopolitisme et de créolisation a connu une avancée considérable au cours des années 90. Pourtant, aucun chercheur ne s’est aventuré à penser ensemble ces deux concepts, ou à les comparer pour en mieux comprendre les modalités respectives. Cet article est un premier pas dans cette direction, ainsi qu’une intervention dans un champ de recherche aujourd’hui en expansion : la “thalassologie” ou l’étude du rôle des voies maritimes dans la construction identitaire des peuples, de l’époque classique jusqu’à nos jours. Je prends ici comme exemple les cultures de l’océan Indien, en particulier celles des îles créoles des Mascareignes, pour suggérer que l’histoire et le quotidien multilingue de cette région peut nous en apprendre beaucoup sur les dynamiques de la mondialisation.

Abstract

A considerable amount of theoretical research has been conducted during the 1990s on the concepts of cosmopolitanism and creolization. Yet, no one has tried either to put these concepts into productive dialogue or to compare them systematically so as to refine current understanding of their respective modalities. This article is an intervention in the emerging field of “thalassology” or “ocean studies”. My goal is to argue for the crucial role of maritime histories in the construction of cultural and national identities over time. My case study is the Creole-speaking Mascarene region of the Indian Ocean and its contributions to the new geonarratives of globalization and universalism.

Index

Mots-clés : cosmopolitiques créoles , créolisation, identités insulaires, Mascareignes, thalassologie

Géographique : Mascareignes

Chronologique : Période contemporaine

Texte intégral

île nous reste les cartes les traces

vies voilées par l’histoire violée […]Diego ton nom sur la carte rayé

Diego amour

Diego amer

Diego à mort…1Michel Ducasse, “île va sang dire”, in Mélangés

New perspectives on the Indian Ocean world have been multiplying. In a recent issue of PMLA, the South African critic Isabel Hofmeyr points out that “the Indian Ocean offers a privileged vantage point from which to track […] what some are calling a ‘post-American’ world2” in which the dominance of the Atlantic is being superseded by the rise of other axes of analysis. I want to echo and complement this approach by bringing into the conversation a concept Hofmeyr does not use despite its importance for an accurate understanding of cultural dynamics in the region: creolization. Her method, which is not uncommon among scholars and theorists of cosmopolitanism, is symptomatic of a tendency to avoid discussions of creolization and its normative theoretical models or empirical variations (e.g. métissage, mestizaje, hybridity) and thus to ignore its conceptual applicability outside fields such as linguistics and anthropology, despite the sustained philosophical, literary, and theoretical engagement carried out by many thinkers over the past three decades3.

Hofmeyr mentions the dialectics of cosmopolitanism and nationalism, imperialism and mobility, old diasporic networks and new public spheres. She acknowledges in a footnote existing research on Indian Ocean creolization and insular cultures. But her argument does not gesture toward the work that the notion of creolization can do to open up the above binaries and the forms of entanglement they hide. She thus misses an opportunity to provide a comprehensive account of old and new colonial dynamics, even though, as she puts it, “[a]t every turn, the Indian Ocean complicates binaries, moving us […] toward a historically deep archive of competing universalisms4”. I support this important statement, but only up to a point. Hofmeyr appears to remain wedded to a view of cosmopolitan universalism that excludes the possibility of its actual transformation–beyond mere competition–in the contact zones of the region and their creolized life worlds. These worlds, shaped by movement along intersecting axes that connected historical nodes of economic activity on land and at sea, remain a crucial part of contemporary geopolitics.

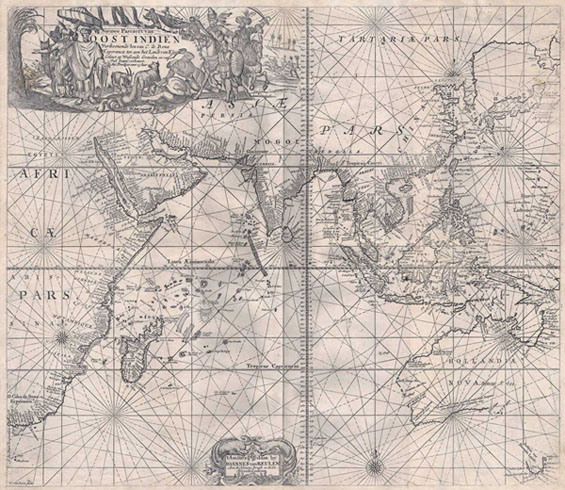

A 1689 Dutch map of the East Indies by Johannes van Keulen helps us visualize the rhizomatic multidirectionality of these axes and imagine new possibilities of encounter in the Indian Ocean rim region (fig. 1). The map concretely plots multiple crossings, each one a “point d’intrication5” (“entanglement6”) with its specific mode of “emmêlement7” (“complex mix8”) at sites where a plurality of possible agents can produce the unpredictable linguistic and social formations characteristic of creolization. The prominent number of islands charted on this map between Madagascar and India reveals the importance they always had for early seafarers.

Fig. 1. Johannes van Keulen, Oost Indien (‘East Indies’), 1689.

Specialists of the Indian Ocean from Auguste Toussaint to Megan Vaughan and Françoise Vergès, all of whom Hofmeyr does acknowledge, have reflected on the paradoxes of creolization, as have critics of South African literary and cultural studies9. The concept has now become influential in trans-Pacific studies10. But it remains a controversial notion11. My goal in this essay is to grasp the reasons that might motivate this generalized diffidence and to suggest greater convergence between the concepts of cosmopolitanism and creolization. I give some concrete examples of overlapping frames of meaning and call for greater understanding of the Creole Indian Ocean, in particular the islands of the Mascarenes and Chagos, which have been directly affected by United States military imperialism in the Persian Gulf.

These Creole archipelagos have served, since the 1970s, as instruments of United States foreign policy in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. Their islands, distant though they are from the western hemisphere, are crucial nodes in the global network of militarized sites that have made perpetual war possible. In 1965, despite local protest, the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) was created by means of the administrative separation of the Chagos islands from Mauritius and the Seychelles, which were due to become independent in the near future12. Between 1968 and 1973, with the help of the United Kingdom, the United States summarily deported some two thousand Chagossians without regard for the self-determination and integrity of either the communities they belonged to or those they were imposed on. These two closely allied nations thus acted as terrorist agents long before 9/11, justifying in the name of global security the forcible displacement of a community that had been rooted in the Chagos for over two centuries, while Americans at home remained ignorant of the historical, linguistic, political, and economic specificities of a region invisible to them. Had the islands of the Indian Ocean been better understood as cosmopolitan crucibles of creolized cultures, would more attention have been paid to their inhabitants’ fate? Nothing is less certain given the islands’ isolated location and small population, the secrecy that surrounds the military facilities in Diego Garcia, and the imperial longue durée behind the use of the Mascarenes, since the early modern period, as strategic pawns in the competing colonial agendas of European empires13.

Shifting alliances among these empires and existing trade routes across the Indian Ocean brought many people into contact for extended periods of time and produced various ‘multiethnic, multireligious and multilingual’ communities whose cosmopolitan character was undeniable14. But it is in fact the term Creole that is primarily used to refer to the region’s islanders and to their languages and cultures. Yet for many scholars the designation Creole continues to imply people without history, located in a geopolitical space that conjures up a tabula rasa or the utopias associated with desert islands.

Judith Butler’s important and lucid reflections in Precarious Life on United States policies of perpetual war come to mind, but in a modified version. “The question that preoccupies me in light of recent global violence”, she writes “is, Who counts as human? Whose lives count as lives? and finally, What makes for a grievable life?15” I want to ask: Who counts as cosmopolitan? Whose lives count as cosmopolitan lives? How do we define a cosmopolitan life in relation to a Creole one? and finally, Is a cosmopolitan life more grievable than a Creole one?

If terms such as diaspora, cosmopolitanism, and creolization can be considered equally useful theoretical models for mapping social realities, why does the general notion of creolization continue to carry a host of troublesome baggage? In particular, how do we think ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘Creole’ together and hope to elicit a revaluation of the notion of creolization and of the producers of Creole cultures, especially those who mourn the loss of their home and must grieve for their dead away from traditional burial sites?

By definition, creolization, like cosmopolitanism, presupposes patterns of movement and degrees of mixing. But apart from a brief discussion by Vergès and my own recent work on Creole cosmopolitics16 and solidarities17, the notions have not been brought into productive confrontation. Robin Cohen’s distinct readers on cosmopolitanism18 and creolization19 are a symptom of this separation that results in the inability to think the concepts together in order to produce a true comparative engagement with the issues they respectively index. As I have argued in my 2012 book, The Known and the Uncertain. Creole Cosmopolitics of the Indian Ocean, we might begin by thinking of creolization as the cosmopolitanism of the subaltern, and cosmopolitanism as the creolization of the elites20. Only then could we see how the question of class has severely hampered the fruitful comparison of these concepts.

If compared at all, the nouns cosmopolitan and Creole and the realities they connote are likely to be seen as polar opposites, belonging to incommensurable coordinates of time and space. The mere fact that I am using capital ‘C’ for Creole and small ‘c’ for cosmopolitan already puts the words into different semantic categories. As a proper noun, Creole refers to a well-defined if not exactly static cultural and linguistic identity (on the model of French or English as proper nouns which identify both a national culture and its language). As both common noun and adjective, cosmopolitan, by contrast, suggests an orientation and an attitude, a habitus and a conscious ethical stance against the limitations of radical territorialism. For David Hansen, “cosmopolitanism implies education rather than just socialization21”. It connotes freedom and is linked to the achievements of rational ethical agents who actively participate in a public culture of refinement and sophistication, of travel and tolerant detachment that is antithetical to the overt or hidden violence of extreme forms of nationalism and chauvinism. The Enlightenment defense of universal rights by the philosophes and their championing of tolerance marks them as cosmopolitan subjects of world culture and benevolent advocates of diversity–an attitude that could however slide into patronizing gestures of self-righteousness, “riddled with racial prejudices against the peoples or cultures they are about–prejudices that are, quite often, only barely disguised in the language of science and philosophy22”. That attitude persists among much of the educated elite’s view of the Creole.

A Creole identity is an accident of birth: a mode of belonging that connects one to a history of coerced contact that produced unpredictable cultural formations and linguistic variations. Creole languages can be erroneously described as dialects, patois, patwah, pidgins, jargons, and “entwisted tongues23”. Michel Degraff (among others, such as Robert Chaudenson24 and Salikoko S. Mufwene25) has argued against “the Fallacy of Creole Exceptionalism” and denounced the prejudices and fantasies of scholars who maintain “dualist assumptions that separate creolistics from the rest of linguistics” and classify Creole languages “apart from ‘normal’/’regular’ languages26”. Primarily oral cultures have been “doomed to inferior status27” because of the material conditions of their emergence in plantation economies. Such negative views easily result in “creolophobia28”, even among creolophones who internalize erroneous foreign views because they lack familiarity with the global array of Creoles: Kreyòl Ayisyen (Haiti), Jamaican Creole, Papiamentu (Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao), Kreol Morisien (Mauritius), Kreyol Reunyoné (Reunion), Sierra Leone Krio, Capeverdian Crioulo, Peranakan Creole (Indonesia), and on the North America continent, Kréyol La Lwizyàn (Louisiana), Gullah (South Carolina) or Chinuk Wawa (Pacific Northwest). The common perception of Creole peoples and languages is still shrouded in ignorance and mired in exotic clichés, in racial mythologies of degeneracy and the deficiencies associated with insularity and slavery, orality, indenture, forcible transplantation or imposed immobility. Haiti is one of the most creative but also most invidious casualties of that history of violent encounters.

Cosmopolitanism, on the other hand, indexes a general or abstract construct applicable to a wide variety of individuals, communities, circumstances, and life worlds. It has elicited a great deal of analytic scrutiny and theoretical unpacking. Hence the many debates about the “ethos of cosmopolitanism29”, the positive and negative valences of cosmopolitanism in relation to nationalism, and the vast array of qualifiers that have been used in recent studies of this concept: “actually existing30”, “discrepant31”, “rooted32”, “vernacular33”, et cetera. Ulrich Beck links it to a particular practice of multilocation, exemplified by those who are “married to several places at once” and thus practice what he calls “place polygamy34”. Cosmopolitan subjects project worldliness, expansiveness, rational decision-making, and orderly accumulation.

If cosmopolitans often claim to understand and even advocate in favor of tolerant diversity, they can also be condescending toward those forms of difference that appear to diverge from established norms of cultural and political rationality that are the signs of an enlightened polity. Such norms pit rationalism against the primitivism of the indigenous and mixed-race populations that largely correspond to the Creoles of both the continental New World and the insular peripheries of former French, British, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and Danish colonies in the Caribbean and Indian Ocean where the realities of creoleness and creolization first emerged. Creoles were the primary target of scientific discourses of degeneration in the nineteenth century, when our disciplines were devised and notions of universalism and particularism became tied to specific social formations by the human sciences that study them. Today, the globalization of cities and national spaces produces instances of creolization and linguistic code switching not unlike those of colonial times35, but these instances tend to be studied under the rubric of cosmopolitanism, globalism, and the generic “cultural mobility36”–not under the rubric of creolization.

In relation to modern norms of identity associated with the emergence of the nation and linked to a legitimate state comprising a relatively homogeneous population, the cosmopolitan subject tends to represent a dubious ontological excess or surplus–personified, since the nineteenth century, by means of clichés, some of them racialized: the rootless intellectual, the wandering Jew, and the transnational banker whose loyalty to a nation-state is in doubt. The Creole subject, by contrast, continues to index a racial, cultural, economic, and linguistic deficit embodied by the illiterate manual or indentured laborer, slave, or economic migrant whose position is ipso facto that of a subject devoid of civilizational quotient and depth. Both the cosmopolitan and the Creole thus appear situated at a similar distance from the national norm but on the plus and minus sides of it, respectively.

The challenge, therefore, is to bring into dialogue intellectual histories that have been viewed as distinct, since the idea of the cosmopolis evokes a highly literate, urbane, and enlightened polity, in contrast to the oral cultures of a Creole world associated with superstition and primitive rituals, from witchcraft and voodoo to varieties of unstable religious syncretism coded as inferior to the ‘purer’ traditions they combine and ‘mix up’. But if we re-think both cosmopolitanism and creolization from the perspective of the insular regions of the Indian Ocean, new possibilities emerge for comparison and redefinition of what it means to be ‘Creole’ and more specifically, a Creole cosmopolitan who participates actively in the construction of cultural meanings through technologies of oral, print, visual, and virtual communication.

The Indian Ocean trade routes that connected the Atlantic to Asia, the Mediterranean to east Africa, the Persian Gulf, south and southeast Asia, the Spice Islands, Formosa/Taiwan, the coast of China and the ports of Japan “lead to an incredible exchange of ideas, technologies, and goods37”. During the nineteenth-century age of sail, ship crews of lascars or lashkari “from every edge of the Indian Ocean” interacted on what Amitav Ghosh has termed “floating Babel[s]38”. They produced a creolized contact language–a mix of Swahili, Malay, Hindustani and Sino-Portuguese-English pidgin39. These lascars were “possibly the first Asians and Africans to participate freely and in substantial numbers, in a globalised workspace40”; they were without question a “richly cosmopolitan group41”, among “the first… to acquire a familiarity with colloquial (as opposed to book-learnt) European languages42”. Conceptually, however, this contact or trade language differs from Creole understood as the mother tongue of a transplanted population that undergoes transformations over time and several generations, in some instances developing African Creole languages rather than European-based ones43. Much comparative work still needs to be done in order to parse out the conceptual issues raised by these linguistic variations.

In addition to this vibrant popular oral culture, printing and book learning also emerged quite early in the archipelagos of the Indian Ocean. In Mauritius, a distinct two-hundred-year-old literary and political culture and the critical discourses it generated dates back to the creation in 1799 of the island’s first literary journal, Le Chroniqueur colonial [The Colonial Chronicler], subtitled Journal politique et littéraire des Isles de France et de la Réunion [Political and Literary Journal of the Isle de France and Reunion]. These developments were made possible by the introduction of the printing press in 1767 (seventeen years before Cape Town received its first press in 178444), which was followed in 1773 by the publication of the island’s first newspaper, Le Cernéen. Initially published as a weekly, it became a daily by the middle of the nineteenth century and is believed to be the second oldest daily French-language newspaper in the world (Le Figaro began in 1825; L’Abeille de la Nouvelle Orléans was founded en 1827, but its publication was interrupted during the Civil War); Le Cernéen’s masthead announces that it was a Mauritian tradition “from 1832 to 1981” (the newspaper is now on-line only). Auguste Toussaint explains that in the Isle de France printing was “entirely a lay enterprise, whereas in most other lands of the Indian Ocean, it began as a missionary enterprise with limited objects45”. It allowed the French but completely multilingual island to take “a place of honour in the history of the progress of printing outside Europe46” given “the existence of conditions favouring the development of an intellectual class to which printing contributed and by which it was itself influenced in its own development47”.

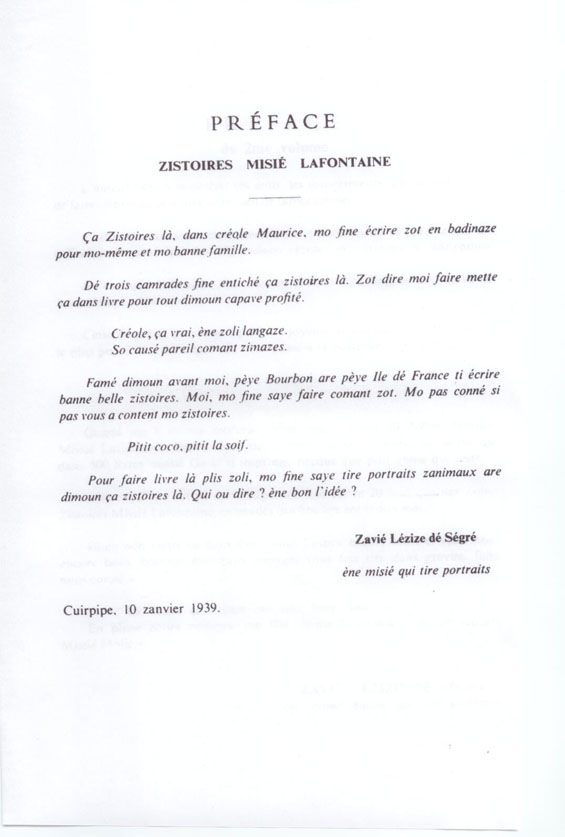

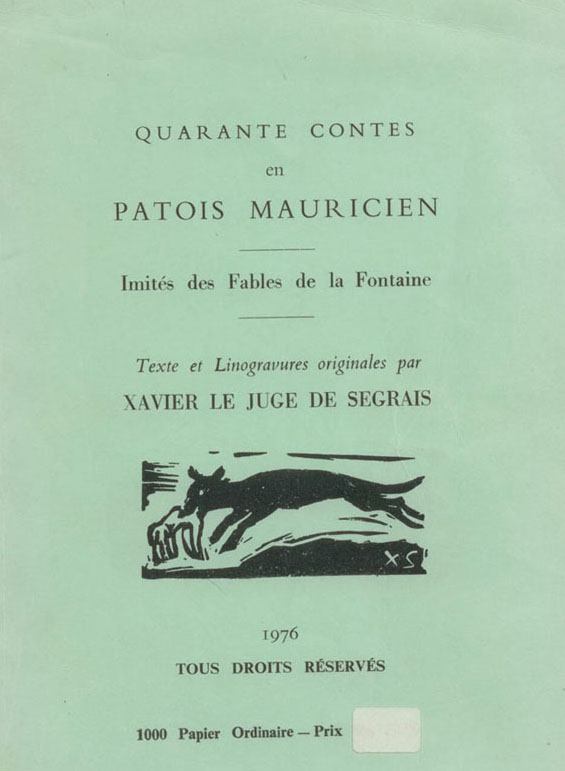

A few revealing examples of this multilingualism: in the mid-nineteenth century, the newspaper Le Mauricien regularly published announcements and articles in Tamil as well as French and English; in 1883, Mirza Ahmod founded the Urdu language Anjuman Islam Maurice; and in 1909, Manilal Doctor, a lawyer originally from Bombay, started a political weekly, The Hindustani, which published contributions in English, Gujarati, and Hindi48. In 1939, Xavier Le Juge de Segrais (in Kreol, Zavié Lézize dé Ségré) published a set of forty fables in Creole ‘imitated’ from those of La Fontaine, Quarante zolies Zistoires Missié Lafontaine, illustrated with beautiful woodcuts and reprinted in 1976 (figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2. A sample of Kreol Morisien, 1939 version (with “Missié” misspelled).

Fig. 3. Illustrated cover of the 1976 limited edition of the 1939 book.

A strong Francophone literary culture developed early, its origins in three related eighteenth-century genres: travel narratives; local responses to these exogenous representations of local peoples, flora, and fauna; and official documents produced by colonial administrators over a century and a half of French rule followed by British rule until independence in 1968. The nineteenth century was marked by an oppositional francophone culture and the proliferation of literary journals49. These provide a unique perspective on processes of world-making that can be defined as both ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘Creole’. Intellectual and critical debates among the literati revolved around the relative merits of two opposing tendencies, versions of which still define postcolonial studies today, namely ‘francotropisme’ and ‘mauricianisme’ or the imitation of French poetic models versus the development of native-born Creole approaches to writing, literary history, and criticism50.

In Reunion Island (aka Bourbon), the Collège Saint-Cyprien, a colonial school established in the 1750s by the French East India Company, was run by Lazarist brothers who recruited students locally but also from the Isle de France and as far away as the Portuguese settlements in India. By 1767, the school had educated more than 160 young men. A 1756 inventory reveals that its library held “no fewer than 2400 books worth 3510 pounds51”. Reading, like theatre going, was an important activity for the elites. The very successful eighteenth-century Creole poets Évariste Parny and Antoine Bertin both attended this school. The renowned astronomer and cartographer Jean-Baptiste Lislet-Geoffroy (1755-1836), on the other hand, was home-schooled in his native Bourbon. The son of an erudite French engineer and a well-educated Senegalese Muslim slave from the kingdom of Galam who was enfranchised at the birth of her son, Lislet-Geoffroy had access at home to a well-stocked library. His personal trajectory exemplifies the kind of early Creole cosmopolitan consciousness I want to underscore here. A talented scientist who assisted the French botanist Philibert Commerson during the latter’s explorations of the islands of Bourbon and Isle de France, Lislet-Geoffroy was elected in 1786 membre correspondant of the Paris Académie Royale des Sciences, though he never set foot in Europe and travelled only around the Indian Ocean52. He was the first non-white member of the Académie. During the English occupation of the island between 1810 and 1815, he was granted British citizenship. Another distinguished cosmopolitan Creole Réunionnais scholar is the twentieth-century Medievalist Joseph Bédier, a major influence on the field53.

Contemporary versions of this mixed-race cosmopolitanism are present in the work of Yves Pitchen, a Lubumbashi-born Mauritian-Belgian photographer who documented the lives of Mauriciens of all backgrounds in the decades following independence. His body of work narrates multiplicities while providing evidence of converging new meanings in the representation of cosmopolitan Creole lives. He points toward new understandings of the realities of creolization and globalization in a post-independence context. One of his most suggestive images captures the contradictions embedded in my project. It is a 1974 photograph of a slender man in his twenties, smartly dressed in his light-colored raincoat, dark pants, shiny shoes, and felt hat (fig. 4). His eyes are wise and knowing; they look directly at the camera. His full mouth shows just a touch of defiance. He is leaning against a carved-wood wardrobe with his left hand in his pocket, posing like a dandy, a white scarf tied a little too neatly around his neck, and peace sign buttons visible on his lapels.

Fig. 4. ‘Prêt à partir sous la pluie’ (‘ready to go into the rain’). By permission of Yves Pitchen.

It is hard to determine the exact ethnic group or groups to which the young man in the photograph belongs: he is light-skinned and of mixed heritage. He has an air of sophistication that belies his modest circumstances, and his class affiliation does not easily map onto familiar western norms. Is he a cosmopolitan or a Creole subject? Knowing the complexity of his national environment, how can we situate him in relation to these two concepts, and does his location alter their received meanings? Does the staging of this photograph open a path that may lead us toward a revision of these terms’ specifically metropolitan meanings, their etymologies, and ideological genealogies? Does it help us understand the conceptual logic that has served to keep them so far apart?

At first glance, the demeanor of the young man conveys a cosmopolitan, jaded elegance that clashes with the modest room in which he is captured on film. One gets the sense that he is aching to break out of the confines of his surroundings, and we understand the feeling of imprisonment that also comes from living in a small, recently independent island of uncertain future, located in the middle of the Indian Ocean. The political and economic difficulties of Mauritius in the 1960s and 1970s generated large-scale out-migrations that coincided with the arrival of the displaced Chagossians and that began to ease up only in the 1990s. Today, Mauritius is thriving, attracting large numbers of rich cosmopolitan South African exiles who have built gated communities protected by armed guards, an unusual residential development for an island where “87 percent of Mauritians own their own homes–without fueling a housing bubble54”. For many locals, the island appears to be losing its soul in the maw of economic globalization.

The image of the young would-be sophisticate conveys the hopes and dreams of the independence generation, just before it began to feel more self-confident about the nation’s options in the new postcolonial world order and ongoing imperial wars. The peace buttons, an expression of solidarity with the people of Vietnam, suggest a lateral or transversal commonality, an ideal of global perpetual peace, in the spirit of a revisited Kantian ideal for a post-imperial world. But if the young man’s overall style and attitude speak of a worldliness or cosmopolitan savvy that is universally legible, there is one unexpected detail in the photograph that produces a different affective response in the viewer who shares or simply recognizes the specificities of the young man’s location in a Creole geography. The man holds in his right hand a small package wrapped in newsprint (probably a loaf of bread), and a tente tiffin or lunch bag made from the woven leaves of the vacoas, a plant common to the tropics and used for centuries by local artisans to make hats, mats, and bags55. This detail makes his worldly demeanor suddenly appear out of place and thus incompatible with the actual resources and boundaries of his condition as a Creole subject (according to the widespread clichés that attach to that designation). The bag connects him to his local environment and its practices of everyday life. This detail interrupts and complicates the image’s message: it corresponds to what Roland Barthes calls the ‘punctum’ of a photograph, an incidental spark of difference that can launch “desire beyond what it permits us to see56”, an accident of representation that changes the overall meaning. This vacoas bag makes poignant the man’s longing for a hypothetical elsewhere beyond the shores of the island. It moves the viewer to take the full measure of his aspirations and its existential contradictions. Yves Pitchen achieves here the subtle intertwining of both global connotations and local particularities that is his trademark.

In her remarkable book Le Silence des Chagos57 [The Silence of the Chagos], Shenaz Patel, a Mauritian writer, captures the harsh realities of forced exile for the Chagossians, providing a concrete cognitive and affective mapping of a small community that fought, for nearly forty years, a losing battle against the super powers58. This sudden exile conforms to the notion of “foundational event59” developed by scholars of the Armenian diaspora and it has produced a lingering memory of catastrophe that marks subsequent generations of Chagossians, as David Constantin’s documentary film makes abundantly clear.

Like the subject of Pitchen’s photograph, Patel’s character Désiré, now grown up, longs for that unknown elsewhere, the country of origin of his matriarchal community, a ‘true diaspora’ in the sense understood by Yves Lacoste: “the dispersion of the major part of a people60”. Born on the vessel Nordvaer, during the last deportees’ transfer to Mauritius in 1973, Desiré can only imagine, from his location in Port Louis–the capital city that refuses to assimilate him–the emptiness his community left behind:

Accoudé à la rambarde de fer qui encercle le port, Désiré scrute l’horizon comme on regarde un écran vide. Les images qu’il voudrait faire surgir s’embrouillent, poudroient et se dissipent dans la réverbération blanche de ce midi qui explose la lumière et écrase les couleurs.

Dans son dos, la ville grouille, passants pressés et véhicules vrombissants, poussière sèche qui lui pique le nez et les yeux.

Le corps tendu en avant, il plonge le regard dans ce ciel dont le bleu se dégrade et jaunit, au loin là-bas, au contact de la mer […].

Partir, enjamber l’eau, traverser l’horizon, défaire cette ligne obstinément fermée pour découvrir ce qu’elle cache, ce qu’on lui cache, à lui, ce dont on le prive, alors que cela lui appartient, alors qu’il en rêve, éveillé comme endormi, depuis que sa mère lui en a parlé61.

Patel’s documentary fiction opens with a poetic description of the Chagos:

C’est une pluie d’îles posées sur la mer. Frangées de sable blanc, un semis de gouttelettes laiteuses qu’on pourrait croire tombées du pis indolent de la Grande Péninsule, dans la traîne des îles Maldives62.

Chagos. Un archipel au nom soyeux comme une caresse, brûlant comme un regret, âpre comme la mort63.

This description is interrupted by the image of a child, far from there, lying next to his dead mother, after United States planes have completed a bombing run, leaving scorched earth behind:

À des kilomètres de là, presque en ligne droite en remontant vers le nord, se découpe une autre terre. Montagneuse, rude, au nom qui siffle. Afghanistan. Un enfant lève les yeux. […] les B52s repartent, allégés de leurs bombes, vers l’océan Indien qu’ils rallieront en quelques minutes à peine, vers leur base là-bas, à Diego Garcia, point de mire des Chagos64.

It is from the facilities on that atoll that the twentieth- and twenty-first-century incursions into Iraq and Afghanistan were launched. It is thanks to high-tech equipment on the ground that Iran, China, Russia as well as countries in Africa and the rest of Asia can easily be kept under surveillance by the United States. It is on that base that a secret CIA detention center is maintained along with the stockpiling of a military arsenal and the regular rotation of air force and navy personnel who come there to enjoy a paradisiacal insular environment.

Despite a 2008 British high court ruling against the Chagossians’ rightful claim to these islands and their territorial waters, the inhabitants, also known as Ilois (a generic colonial term they reject65) still harbor the hope of return and continue to fight for it in international courts. In a leaked confidential cable, made public by Wikileaks in 2010, the United Kingdom proposed in 2009 that the entire Chagos archipelago become a protected ecological zone or marine biosphere as a means of preventing the former inhabitants and their descendants from ever returning to what many of them, whether living in Mauritius, the Seychelles, or Europe, still consider home. In a cynical move that epitomizes the contradictions of contemporary conservation efforts and the hypocritical environmentalist policies of powerful nations, and thus echoes and furthers the “green imperialism66” of earlier colonial times, the United Kingdom contended that to establish this archipelago as the world’s largest marine park would definitively safeguard United States strategic and military interests in the region and put to rest, once and for all, the resettlement claims of these Creole-speaking peoples. Britain led the effort to declare the Chagos an environmental preservation and protection zone for global biodiversity.

Is marine life more grievable than the disappearance of a Creole community? Rooted there for more than two centuries, the community had caused no harm to the fauna and flora. Why does the fate of the Chagossians, whose forcible displacement directly serves United States political interests, remain largely invisible in North America despite the novel (Le Silence des Chagos), documentary films67, exhibition (Kréyol Factory), and, most recently, comprehensive history68 and anthropological study69 that have been devoted to it? Would a better understanding of the cosmopolitan origins of Creole cultures in the region help reframe perceptions? The Portuguese, French, Indian, English, and Creole toponyms of the Chagos archipelago bear the traces of their cosmopolitan history: Diego Garcia, Peros Banhos, Saint Brandon, Île Gabrielle, Benares Shoal, Ganges Bank, Blenheim Reef, Solomon, Moresby, Tit’île Mapou, and so on. First mapped by the Portuguese explorers Mascarehnas and Albuquerque, the Chagos, like the Mascarene Islands to the south, were subsequently settled by the French, then by the English. They became home to Europeans, Africans, and Asians and so to an ethnically diverse mix of creolized multilingual populations whose concrete experiences of “actually existing cosmopolitanisms70” can serve to modify the parameters by which scholars construct the idea of the cosmopolitan.

The scholarly turn to the Indian Ocean heralded by Hofmeyr is a welcome development if it also signals greater awareness of the layered political and cultural legacies of the Creole populations and their contributions to world history, music, literature, and visual culture. It would be regrettable if this turn simply became another opportunity to study only the competing histories of emerging Anglophone (and yet also multilingual) powers (India, South Africa) in their respective face off with more established nation-states (the United States, the United Kingdom, and France). As new geonarratives of globalization and universalism begin to cast longer shadows on some of the smallest and most diverse human environments of the planet, greater attention to the specificities of creolization can help clarify what is at stake and yet remains hidden in the “terraqueous71” politics of place and space and in what historians are now calling “the new thalassology72” that is reconfiguring global studies in terms of maritime histories.

Notes de bas de page numériques

1 “islands only maps left only traces/ lives veiled by violated history […] / Diego your name crossed out on the map / Diego sweet love / Diego bitter sweet / Diego till death…” All translations are mine unless otherwise indicated.

2 Isabel Hofmeyr, “Universalizing the Indian Ocean”, PMLA,vol. 125, no 3, 2010, p. 721.

3 For recent approaches, see Doris L. Garraway, The Libertine Colony: Creolization in the Early French Caribbean (Durham, Duke University Press, 2005) and Christopher GoGwilt, The Passage of Literature: Genealogies of Modernism in Conrad, Rhys, and Pramoedya (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011) among many others.

4 Isabel Hofmeyr, “Universalizing the Indian Ocean”, p. 722.

5 Édouard Glissant, Le Discours antillais, Paris, Le Seuil, 1981, p. 36.

6 Édouard Glissant, Caribbean Discourse (Trans. J. Michael Dash), Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia, 1989, p. 26.

7 Édouard Glissant, Poétique de la Relation, Paris, Gallimard, 1990, p. 103.

8 Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Trans. Betsy Wing), Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1997, p. 89.

9 See, for example, Sarah Nuttall, Entanglement: Literary and Cultural Reflections on Post-Apartheid, Johannesburg, Wits University Press, 2009.

10 See Françoise Lionnet and Shu-mei Shih (eds.), The Creolization of Theory, Durham, Duke University Press, 2011, and Takeshi Matsuda, The Age of Creolization in the Pacific: In Search of Emerging Cultures and Shared Values in the Japan-America Borderlands, Hiroshima, Keisuisah, 2001.

11 See Stephan Palmié, “Creolization and Its Discontents”, Annual Review of Anthropology, no 35, 2006, pp. 433-456.

12 See Jocelyn Chan Low, “The Making of the British Indian Ocean Territory: A Forgotten Tragedy”, in Shawkat Toorawa (ed.), The Western Indian Ocean: Essays on Islands and Islanders, Port Louis, Toorawa Trust, 2007, pp. 102-126.

13 See Rie Koike, “From French-British Colonial Coconut Plantations to UK-Europe Citizenship: The Chagos as a Special Case of Colonial Legacy”, in Vinesh Hookoomsing (ed.), Isle de France, Mauritius: 1810, The Great Turning Point, Mauritius, AIEFCOI, in press.

14 See Akhil Gupta “Globalisation and Difference: Cosmopolitanism Before the Nation-State”, Transforming Cultures eJournal, vol. 3, no 2, 2008, p. 10.

15 Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence, London, Verso, 2004, p. 20.

16 Françoise Lionnet (ed.), “Introduction: ‘Between Words and Images: The Culture of Mauritius’”, International Journal of Francophone Studies, vol. 13, no 3-4, Special Issue, 2011.

17 Françoise Lionnet, “Continents and Archipelagoes: From E Pluribus Unum to Creole Solidarities”, PMLA, vol. 123, no 5, 2008, pp. 1503-1515.

18 See Steven Vertovec and Robin Cohen (eds.), Conceiving Cosmopolitanism: Theory, Context and Practice, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002.

19 See Robin Cohen and and Paola Toninato (eds.), The Creolization Reader: Studies in Mixed Identities and Cultures, Oxford, Routledge, 2010.

20 Françoise Lionnet, The Known and the Uncertain. Creole Cosmopolitics of the Indian Ocean, Trou d’Eau Douce. L’Atelier d’écriture, 2012, “Essais et Critiques Littéraires”, p. 65.

21 David T. Hansen, “Chasing Butterflies Without a Net: Interpreting Cosmopolitanism”, Studies in Philosophy and Education, no 29, 2010, p. 164.

22 Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze (ed.), “Introduction”, in Race and the Enlightenment. A Reader, Oxford, Blackwell, 1997, p. 1.

23 See George Lang, Entwisted Tongues: Comparative Creole Literatures, Amsterdam, Rodopi, 2000.

24 See Robert Chaudenson, Des Îles, des hommes, des langues : Essai sur la créolisation linguistique et culturelle, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1992.

25 See Salikoko S. Mufwene, The Ecology of Language Evolution, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

26 Michel Degraff, “Linguists’ Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Creole Exceptionalism”, Language in Society, vol. 34, no 4, 2005, p. 537.

27 George Lang, Entwisted Tongues: Comparative Creole Literatures, p. 17.

28 George Lang, Entwisted Tongues: Comparative Creole Literatures, p. 16.

29 Tim Brennan, At Home in the World: Cosmopolitanism Now, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 10.

30 Scott L. Malcomson, “The Varieties of Cosmopolitan Experience”, in Pheng Cheah and Bruce Robbins (eds.), Cosmopolitics: Thinking and Feeling Beyond The Nation, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1998, p. 240.

31 James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 36.

32 K. Anthony Appiah, The Ethics of Identity, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2005, p. 213.

33 Homi Bhabha, “Unsatisfied: Notes on Vernacular Cosmopolitanism”, in Peter C. Pfeiffer and Laura Garcia-Moreno (eds.) Text and Narration, Columbia, Camden, 1996, p. 191.

34 See Ulrich Beck, What is Globalization? (Trans. Patrick Camiller), Cambridge, Polity, 2000, pp. 72-77.

35 See Édouard Glissant, “L’Europe et les Antilles : une interview d’Édouard Glissant” (interview by Andrea S. Hiepko), Mots Pluriels, no 8, 1998.

36 See Stephen Greenblatt with Ines Zupanov et al., Cultural Mobility. A Manifesto, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

37 Akhil Gupta “Globalisation and Difference: Cosmopolitanism Before the Nation-State”, p. 8.

38 Amitav Ghosh, “Of Fanás and Forecastles: The Indian Ocean and Some Lost Languages of the Age of Sail”, in Pamela Gupta, Isabel Hofmeyr and Michael Pearson (eds.), Eyes Across the Water: Navigating the Indian Ocean, Johannesburg, Unisa, 2010, p. 17.

39 Amitav Ghosh, “Of Fanás and Forecastles: The Indian Ocean and Some Lost Languages of the Age of Sail”, pp. 23-24.

40 Amitav Ghosh, “Of Fanás and Forecastles: The Indian Ocean and Some Lost Languages of the Age of Sail”, p. 19.

41 Amitav Ghosh, “Of Fanás and Forecastles: The Indian Ocean and Some Lost Languages of the Age of Sail”, p. 16.

42 Amitav Ghosh, “Of Fanás and Forecastles: The Indian Ocean and Some Lost Languages of the Age of Sail”, p. 19.

43 See Pier M. Larson, Ocean of Letters: Language and Creolization in an Indian Ocean Diaspora, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 10-12, and Vijaya Teelock, “The Influence of Slavery in the Formation of Creole Identity”, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, vol. 19, no 2, 1999, p. 7.

44 See Auguste Toussaint, Early Printing in the Mascarene Islands. 1767-1810, Paris, Durassié, 1951, p. 21.

45 Auguste Toussaint, Early Printing in Mauritius, Réunion, Madagascar and the Seychelles, Amsterdam, Van Gendt, 1969, p. 9.

46 Auguste Toussaint, Early Printing in Mauritius, Réunion, Madagascar and the Seychelles, p. 27.

47 Auguste Toussaint, Early Printing in Mauritius, Réunion, Madagascar and the Seychelles, p. 9.

48 Auguste Toussaint, Early Printing in Mauritius, Réunion, Madagascar and the Seychelles, p. 51.

49 See Vicram Ramharai, “Dynamique des revues littéraires à la fin du XIXe siècle et au début du XXe siècle à Maurice”, in Norbert Dodille (ed.), Idées et représentations coloniales dans l’océan Indien, Paris, PUPS, 2009, p. 555.

50 See Evelyn Kee Mew, “La littérature mauricienne et les débuts de la critique”, in Françoise Lionnet (ed.) “Between Words and Images: The Culture of Mauritius”, International Journal of Francophone Studies, vol. 13, no 3-4, Special Issue, 2011, p. 423.

51 Olivier Caudron, “Esquisse d’une histoire intellectuelle des îles Mascareignes aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles”, in Paolo Carile (ed.), Sulla via delli Indie Orientali: Aspetti della francofonia nell’Oceano Indiano / Sur la route des Indes Orientales: Aspects de la francophonie dans l’océan Indien, Fasano, Schena, 1995, p. 346.

52 See Emmanuel Richon, “Portrait de Jean-Baptiste Lislet-Geoffroy”: http://www.potomitan.info/galerie/geoffroy/index.php .

53 See Michelle R. Warren, Creole Medievalism: Colonial France and Joseph Bédier’s Middle Ages, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

54 Joseph E. Stieglitz, “The Greatest Country on Earth: What The United States Can Learn From the Tiny Island Nation of Mauritius”, Slate, 7 March 2011.

55 For a fascinating historical account of the links between the vacoas plant (or vakwá [Malagasy] and vaquois [French]) and the mythical island of Waqwaq or al-Waqwâq in medieval Arabic literature, especially in the Andalusian philosopher Ibn Tufayl’s allegorical work, see Shawkat Toorawa, “Cartographies (of Silence), Orientation, and Sexuality: The Discovery of the Americas and the Mascarenes”, in Susan R. Crystal (ed.), U. S. A. –Mauritius 200 Years: Trade, History, Culture, Moka, Mahatma Gandhi Institute, 1996, and Shawkat Toorawa (ed.), The Western Indian Ocean: Essays on Islands and Islanders, Port Louis, Toorawa Trust, 2007.

56 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, New York, Hill, 1981, p. 59.

57 Shenaz Patel, Le Silence des Chagos, Paris, L’Olivier, 2005.

58 See Véronique Bragard, “Murmuring Vessels: Relocating Chagossian Memory and Testimony in Shenaz Patel’s Le Silence des Chagos”, in Julia Waters (ed.), “‘L’ici et l’ailleurs’: Postcolonial Literatures of the Francophone Indian Ocean”, e-France: an on-line Journal of French Studies, no 2, 2008.

59 Martine Hovanessian, “La notion de diaspora : usages et champ sémantique”, Journal des anthropologues, no 72-73, 1998, p. 17.

60 Yves Lacoste, “Éditorial : Géopolitique des diasporas”, Hérodote, no 53, April-June 1989, p. 3.

61 Shenaz Patel, Le Silence des Chagos, pp. 114-115: “Elbows on the metal guardrail that runs along the harbour, Désiré scrutinizes the horizon the way one looks at an empty screen. / Behind him, the city is bustling with hurried pedestrians and noisy vehicles. A dry dust irritates his nose and eyes. / His body bent forward, his gaze pierces the fading blue sky that turns yellow in the distance where it meets up with the sea […]. / To leave, jump over the water, cross the horizon, break through that stubborn line and open it up to find out what it hides, what they are hiding from him, what they are keeping from him even though it belongs to him and he dreams about it, whether awake or asleep, ever since his mother told him about it”.

62 Shenaz Patel, Le Silence des Chagos, p. 9: “It is a dusting of islands on the sea, fringed with white sand, a sprinkling of milky drops that seem to be falling from the lazy udder of the South Asian Peninsula, in the wake of the Maldives”.

63 Shenaz Patel, Le Silence des Chagos, p. 10: “Chagos. An archipelago with a name as silky as a caress, as burning as a regret, as harsh as death itself”.

64 Shenaz Patel, Le Silence des Chagos, p. 10: “Kilometers away from there, almost in a straight line to the north, another country rises. Mountainous, it has a name that whistles. Afghanistan. A child looks up. […] the B52s are leaving, lighter without their bombs, on their way back to the Indian Ocean where they will land in just a few minutes, over there, on their base in Diego Garcia, their destination in the Chagos”.

65 They claim the name Chagossiens for themselves (See Jean-Yves Chavrimootoo, “Davantage de considérations réclamées pour les descendants des Chagossiens”, L’Express, 20 April 2011).

66 See Richard Grove, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600-1860, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

67 David Constantin, Diego l’interdite, Caméléon Productions, 2007, and John Pilger, Stealing a Nation, Community Video, 2004.

68 Sandra J. T. M. Evers and Marry Kooy (eds.), Eviction from the Chagos Islands, Leiden, Brill, 2011.

69 David Vine, Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U. S. Military Base in Diego Garcia, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2009.

70 See Scott L. Malcomson, “The Varieties of Cosmopolitan Experience”, p. 240, and Françoise Lionnet and Thomas Spear, “Introduction: Mauritius in/and Global Culture”, International Journal of Francophone Studies, vol. 13, no 3-4, 2011, p. 379.

71 See Margaret Cohen, “Literary Studies and the Terraqueous Globe”, PMLA,vol. 125, no 3, 2010, pp. 657-662.

72 See Markus P. M. Vink, “Indian Ocean Studies and the ‘New Thalassology’”, Journal of Global History, vol. 2, no 1, 2007, pp. 41-62.

Bibliographie

Works cited

APPIAH K. Anthony, The Ethics of Identity, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2005.

BARTHES Roland, Camera Lucida, New York, Hill, 1981.

BECK Ulrich, What is Globalization? (Trans. CAMILLER Patrick), Cambridge, Polity, 2000 [Was ist Globalisierung?, Frankfurt, Suhrkamp, 1997].

BHABHA Homi, “Unsatisfied: Notes on Vernacular Cosmopolitanism”, in PFEIFFER Peter C. and GARCIA-MORENO Laura (eds.), Text and Narration, Columbia, Camden, 1996, pp. 191-207.

BRAGARD Véronique, “Murmuring Vessels: Relocating Chagossian Memory and Testimony in Shenaz Patel’s Le Silence des Chagos”, in WATERS Julia (ed.), “‘L’ici et l’ailleurs’: Postcolonial Literatures of the Francophone Indian Ocean”, e-France: an on-line Journal of French Studies, no 2, 2008: http://www.reading.ac.uk/e-france/Indian%20Ocean/Bragard.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2012).

BRENNAN Tim, At Home in the World: Cosmopolitanism Now, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1997.

BUTLER Judith, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence,London, Verso, 2004.

CAUDRON Olivier, “Esquisse d’une histoire intellectuelle des îles Mascareignes aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles”, in CARILE Paolo (ed.), Sulla via delli Indie Orientali: Aspetti della francofonia nell’Oceano Indiano / Sur la route des Indes Orientales: Aspects de la francophonie dans l’océan Indien, Fasano, Schena, 1995, pp. 341-396.

CHAN LOW Jocelyn, “The Making of the British Indian Ocean Territory: A Forgotten Tragedy”, in TOORAWA Shawkat (ed.), The Western Indian Ocean: Essays on Islands and Islanders, Port Louis, Toorawa Trust, 2007, pp. 102-126.

CHAUDENSON Robert, Creolization of Language and Culture (Ed. and trans. MUFWENE Salikoko S. et al.), London, Routledge, 2001 [Des Îles, des hommes, des langues : Essai sur la créolisation linguistique et culturelle, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1992].

CHAVRIMOOTOO Jean-Yves, “Davantage de considérations réclamées pour les descendants des Chagossiens”, L’Express. 20 April 201: http://www.lexpress.mu/story/23491-davantage-de-considerations-reclamees-pour-les-descendants-des-chagossiens.html (accessed on 11 May 2011).

CLIFFORD James, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1997.

COHEN Margaret, “Literary Studies and the Terraqueous Globe”, PMLA, vol. 125, no 3, 2010, pp. 657-662.

COHEN Robin, “Social Identities and Creolization”, in KNOTT Kim and MCLOUGHLIN Séan (eds.), Diasporas: Concepts, Intersections, Identities, London, Zed, 2010, pp. 69-73.

COHEN Robin and TONINATO Paola (eds.), The Creolization Reader: Studies in Mixed Identities and Cultures, Oxford, Routledge, 2010.

CONSTANTIN David, Diego l’interdite, Caméléon Productions, 2007.

DEGRAFF Michel, “Linguists’ Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Creole Exceptionalism”, Language in Society, vol. 34, no 4, 2005, pp. 533-591.

DUCASSE Michel, Mélangés, Maurice, Vilaz Métiss, 2012.

EVERS Sandra J. T. M. and KOOY Marry (eds.), Eviction from the Chagos Islands, Leiden, Brill, 2011.

EZE Emmanuel Chukwudi (ed.), “Introduction”, in Race and the Enlightenment. A Reader, Oxford, Blackwell, 1997, pp. 1-9.

GARRAWAY Doris L., The Libertine Colony: Creolization in the Early French Caribbean, Durham, Duke University Press, 2005.

GHOSH Amitav, “Of Fanás and Forecastles: The Indian Ocean and Some Lost Languages of the Age of Sail”, in GUPTA Pamela, HOFMEYR Isabel and PEARSON Michael (eds.), Eyes Across the Water: Navigating the Indian Ocean,Johannesburg, Unisa, 2010, pp. 15-31.

GLISSANT Édouard, Le Discours antillais, Paris, Le Seuil, 1981.

GLISSANT Édouard, Caribbean Discourse (Trans. DASH J. Michael), Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia, 1989.

GLISSANT Édouard, Poétique de la Relation, Paris, Gallimard, 1990.

GLISSANT Édouard, Poetics of Relation (Trans. WING Betsy), Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1997.

GLISSANT Édouard, “L’Europe et les Antilles : une interview d’Édouard Glissant” (interview by HIEPKO Andrea S. Hiepko), Mots Pluriels, no 8, 1998.

GOGWILT Christopher, The Passage of Literature: Genealogies of Modernism in Conrad, Rhys, and Pramoedya, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011.

GREENBLATT Stephen with ZUPANOV Ines et al., Cultural Mobility. A Manifesto, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

GROVE Richard, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600-1860, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

GUPTA Akhil, “Globalisation and Difference: Cosmopolitanism Before the Nation-State”, Transforming Cultures eJournal, vol. 3, no 2, 2008, pp. 1-20.

HANSEN David T., “Chasing Butterflies Without a Net: Interpreting Cosmopolitanism”, Studies in Philosophy and Education, no 29, 2010, pp. 151-166.

HOVANESSIAN Martine, “La notion de diaspora : usages et champ sémantique”, Journal des anthropologues, no. 72-73, 1998, p. 11-29.

HOFMEYR Isabel, “Universalizing the Indian Ocean”, PMLA, vol. 125, no 3, 2010, pp. 721-722.

KEE MEW Evelyn, “La littérature mauricienne et les débuts de la critique”, in LIONNET Françoise (ed.), “Between Words and Images: The Culture of Mauritius”, International Journal of Francophone Studies, vol. 13, no 3-4, Special Issue, 2011, pp. 417-433.

KOIKE Rie, “From French-British Colonial Coconut Plantations to UK-Europe Citizenship: The Chagos as a Special Case of Colonial Legacy”, in HOOKOOMSING Vinesh (ed.), Isle de France, Mauritius: 1810, The Great Turning Point, Mauritius, AIEFCOI, in press.

KRÉYOL FACTORY, Des artistes interrogent les identités créoles, Paris, Parc de la Villette, 2009.

LACOSTE Yves, “Éditorial : Géopolitique des diasporas”, Hérodote, no 53, April-June 1989, pp. 3-12.

LANG George, Entwisted Tongues: Comparative Creole Literatures, Amsterdam, Rodopi, 2000.

LARSON Pier M., Ocean of Letters: Language and Creolization in an Indian Ocean Diaspora, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

LIONNET Françoise, “Continents and Archipelagoes: From E Pluribus Unum to Creole Solidarities”, PMLA, vol. 123, no 5, 2008, pp. 1503-1515.

LIONNET Françoise (ed.), “Between Words and Images: The Culture of Mauritius”, International Journal of Francophone Studies, vol. 13, no 3-4, Special Issue, 2011.

LIONNET Françoise, The Known and the Uncertain. Creole Cosmopolitics of the Indian Ocean, Trou d’Eau Douce, L’Atelier d’écriture, 2012, “Essais et Critiques Littéraires”.

LIONNET Françoise and SHIH Shu-mei (eds.), The Creolization of Theory, Durham, Duke University Press, 2011.

LIONNET Françoise and SPEAR Thomas, “Introduction: Mauritius in/and Global Culture”, International Journal of Francophone Studies, vol. 13, no 3-4, 2011, pp. 371-400.

MALCOMSON Scott L., “The Varieties of Cosmopolitan Experience”, in CHEAH Pheng and ROBBINS Bruce (eds.), Cosmopolitics: Thinking and Feeling Beyond The Nation, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1998, pp. 233-245.

MATSUDA Takeshi, The Age of Creolization in the Pacific: In Search of Emerging Cultures and Shared Values in the Japan-America Borderlands, Hiroshima, Keisuisah, 2001.

MUFWENE Salikoko S., The Ecology of Language Evolution, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

NUTTALL Sarah, Entanglement: Literary and Cultural Reflections on Post-Apartheid, Johannesburg, Wits University Press, 2009.

PALMIÉ Stephan, “Creolization and Its Discontents”, Annual Review of Anthropology, no 35, 2006, pp. 433-456.

PATEL Shenaz, Le Silence des Chagos, Paris, L’Olivier, 2005.

PILGER John, Stealing a Nation, Community Video, 2004.

PITCHEN Yves, Mauriciens, Brussels, Husson, 2006.

RAMHARAI Vicram, “Dynamique des revues littéraires à la fin du XIXe siècle et au début du XXe siècle à Maurice”, in DODILLE Norbert (ed.), Idées et représentations coloniales dans l’océan Indien, Paris, PUPS, 2009, pp. 551-567.

RICHON Emmanuel, “Portrait de Jean-Baptiste Lislet-Geoffroy”: http://www.potomitan.info/galerie/geoffroy/index.php (accessed on 9 June 2011).

STIEGLITZ Joseph E., “The Greatest Country on Earth: What The United States Can Learn From the Tiny Island Nation of Mauritius”, Slate, 7 March 2011.

TEELOCK Vijaya, “The Influence of Slavery in the Formation of Creole Identity”, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, vol. 19, no 2, 1999, pp. 3-8.

TOORAWA Shawkat, “Cartographies (of Silence), Orientation, and Sexuality: The Discovery of the Americas and the Mascarenes”, in CRYSTAL Susan R. (ed.), U. S. A.–Mauritius 200 Years: Trade, History, Culture, Moka, Mahatma Gandhi Institute, 1996.

TOORAWA Shawkat (ed.), The Western Indian Ocean: Essays on Islands and Islanders, Port Louis, Toorawa Trust, 2007.

TOUSSAINT Auguste, Early Printing in the Mascarene Islands. 1767-1810, Paris, Durassié, 1951.

TOUSSAINT Auguste, Early Printing in Mauritius, Réunion, Madagascar and the Seychelles, Amsterdam, Van Gendt, 1969.

VAUGHAN Megan, Creating the Creole Island: Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Mauritius, Durham, Duke University Press, 2005.

VERGÈS Françoise, “Vertigo and Emancipation, Creole Cosmopolitanism and Cultural Politics”, Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 18, no 2-3, 2001, pp. 169-183.

VERTOVEC Steven and COHEN Robin (eds.), Conceiving Cosmopolitanism: Theory, Context and Practice, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002.

VINE David, Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U. S. Military Base in Diego Garcia, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2009.

VINK Markus P. M., “Indian Ocean Studies and the ‘New Thalassology’”, Journal of Global History, vol. 2, no 1, 2007, pp. 41-62.

WARREN Michelle R., Creole Medievalism: Colonial France and Joseph Bédier’s Middle Ages, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Pour citer cet article

Françoise Lionnet, « Cosmopolitan or Creole Lives? Globalized Oceans and Insular Identities », paru dans Loxias-Colloques, 3. D’une île du monde aux mondes de l’île : dynamiques littéraires et explorations critiques des écritures mauriciennes, Cosmopolitan or Creole Lives? Globalized Oceans and Insular Identities, mis en ligne le 28 mai 2013, URL : http://revel.unice.fr/symposia/actel/index.html?id=450.

Auteurs

Françoise Lionnet est professeure de littératures françaises, francophones et comparées à UCLA où elle dirige également le Centre d’études africaines. Elle a publié de nombreux articles et plusieurs ouvrages, dont Autobiographical Voices: Race, Gender, Self-Portraiture (1989), Postcolonial Representations: Women, Literature, Identity (1995) ; les volumes collectifs Minor Transnationalism (2005), The Creolization of Theory (2011); et plus récemment Écritures féminines et dialogues critiques. Subjectivité, genre et ironie (2012) et Le Su et l’incertain. Cosmopolitiques créoles de l’océan Indien (2012).